A 12-year-old boy was shot running from a Native boarding school. His tribe mourns him today

This is the first in a series of stories KUOW is publishing on the Native boarding school experience in the Pacific Northwest. It contains depictions of abuse and violence against children.

Part I: the store theft

Charlie Fiester was hungry.

It had been a week since the Klamath boy had run away from Chemawa Indian School, a boarding school in Oregon notorious for its cruelty against Native children. It was his fourth time trying to get away.

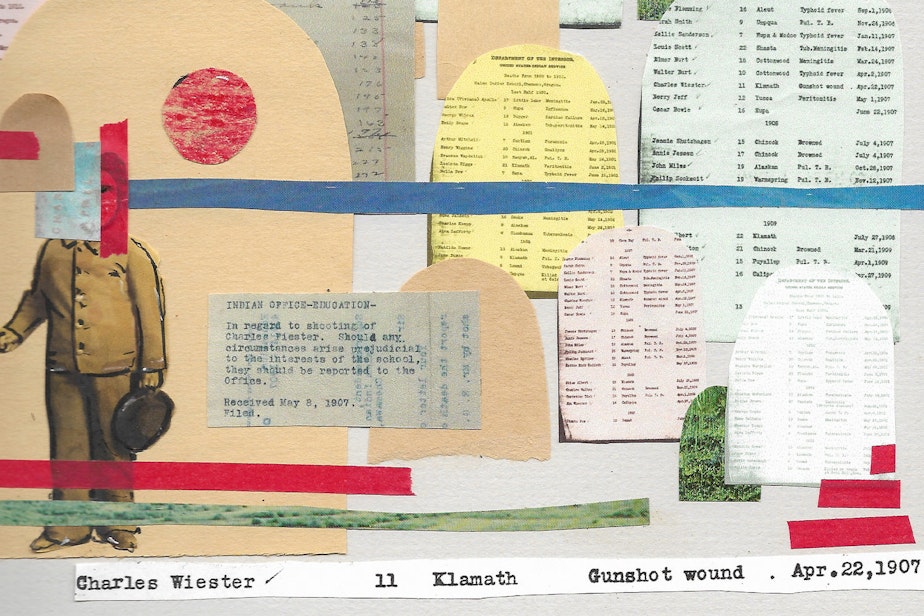

He was one of hundreds of children who had fled the school and its bleak conditions around that time, in the early 1900s. Records show that at least 270 Native children died of tuberculosis and other diseases while at Chemawa. Some died while running away.

Charlie camped out near a barn by the river with his buddies Ignace Seymour and Willie Wiley — both 13. The three boys soothed hunger pangs by eating eggs, spuds, and stolen chickens.

It was April 1907, and Willie had another idea for getting food. The month before, he’d broken into a store owned by Robert Henderson, also the postmaster and telegraph operator. Henderson had caught Willie hiding behind sacks of flour, which could have added up to 15 years of prison time for Willie, but instead, Henderson shooed him away.

Breaking in was a risk, but hungry boys take chances. So at half past midnight, they crept up from the river to the store, dreaming of oranges and candy. Willie also planned on swiping chewing tobacco for himself.

Nearby, they found an ax and used it to try to pry open the door.

Henderson — a light sleeper and on edge about break-ins — woke up, and called out, “Who’s there?” He opened his second-floor window and yelled into the cool night air, “Stop!”

The boys didn’t hear him, because at that moment, a train rumbled by.

Still, they sensed something was amiss and started to run, jumping over a fence to get away.

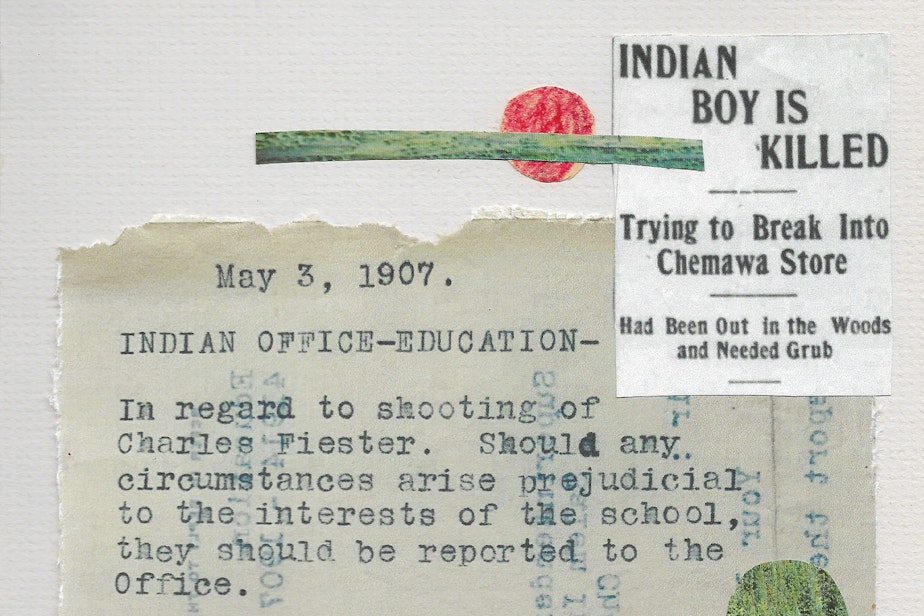

In the dark, Henderson made out a small figure. He later told the sheriff that he assumed it was a Japanese railway worker.

Henderson pulled out his pistol and took aim…

We want to hear your stories. If you would like to share your experience with Native boarding schools in the Pacific Northwest, please email boardingschools@kuow.org.

P

art II: Chemawa Indian School

Charlie’s story lives in records housed at the National Archives in Seattle and on hard drives belonging to researchers. They include transcripts of witness testimony, runaway records, letters from home, superintendent correspondence, inspectors’ reports, newspaper articles, admission logs, and a list of child deaths from the Department of Interior.

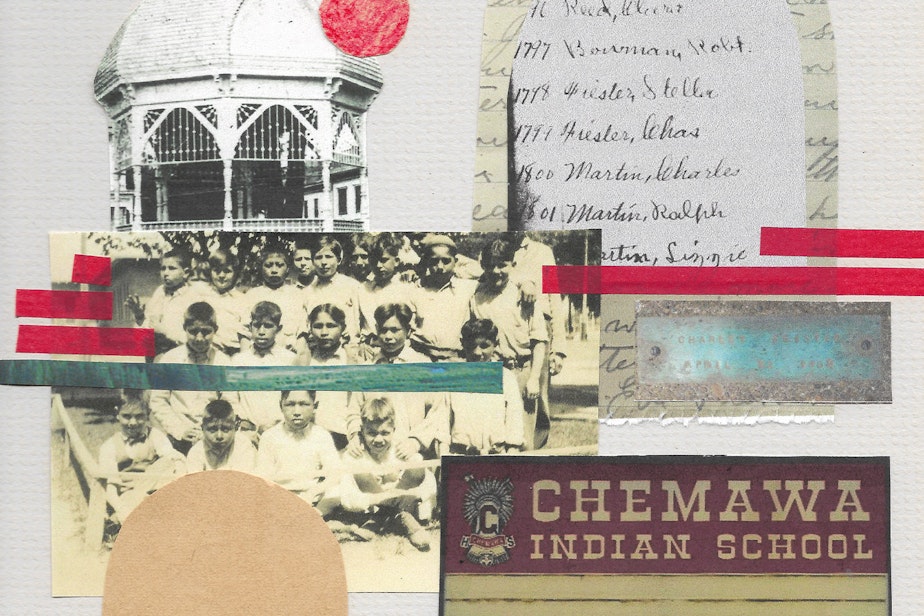

Records show that Charlie arrived at the school when he was 6, on the same day as 9-year-old Stella Fiester, who was likely his big sister, given the information recorded.

The records show that like Charlie, many fled from the Chemawa Indian School, an institution used as a genocidal tool of the federal government to stamp out Native American culture and identity.

Opening in 1880 in Forest Grove, the school’s first students came from the Puyallup and Nisqually tribes in Washington state; eventually, children from Alaska and California were forced to attend the school. In 1885, the school moved to the north of Salem.

Abuse and the school’s cramped and poor conditions drove students to flee. At Chemawa, from 1904 through 1909, at least 319 students ran away, according to a roster of runaways that listed students by name and each date they fled.

Some children ran away eight times.

Children went hungry, records show; the school was run in a military fashion; disease was rampant, and student deaths were not uncommon. A cemetery remains near Chemawa.

When students ran, local police officers were often those who tracked down the runaways and jailed them until someone from the school picked them up. Children who ran could be whipped or paddled as punishment.

Survivors of Chemawa detailed instances of corporal punishment and sexual abuse into the 1950s.

Lawney Reyes, a Seattle-based, American Sin-Aikst artist and writer, wrote in his memoir White Grizzly Bear's Legacy: Learning to be Indian, of abuse at the school from 1940 to 1942.

A matron’s assistant would examine children for cleanliness after they bathed and used a brush to scrub behind their ears, sometimes until they bled, Reyes wrote. When someone broke the rules, they would be punished with either additional chores or forced to run the gauntlet, while other children beat them with belts. Reyes died last August.

Superintendent Edwin Chalcraft headed the school during Charlie’s time. Hired by the federal Office of Indian Affairs in 1883, Chalcraft spent four decades working at boarding schools across the Pacific Northwest. Parents often wrote him letters urging him to release their children. Some parents hadn’t seen their children in years. These requests were frequently denied or ignored.

One parent wrote 33 times without receiving a response.

Among those pleading with Chalcraft was Willie Wiley’s mother, who lived in Seattle. Wiley was Chinook, according to Chemawa records.

“I have a good home now and can care for him,” she wrote to Chalcraft in August of 1905. “Hoping you will grant a mother’s wish.”

Six years later, she wrote again. “I have written several times. I want you to send him home at once … he has not seen his mother for nine years. I think he surely would like to see me.”

In a letter to Willie, she reassured him that she still wanted him home. “Did you think your mother had forgotten you, my dear little boy?”

It’s unclear from the records if Willie received the letter. It appears parent letters were put in students’ files, rather than given to them.

A mother living in Seaside, Oregon, circulated a petition asking that Chalcraft release her daughter. The mother used the word “inmate” to describe her daughter. Four months later, a lawyer sent a letter on the mother’s behalf, asking again that her child be allowed home.

The child was sent home for a temporary visit, and her mother notified Chalcraft that she would not be returning. It was a bold move, as local police were often tasked with kidnapping children out of their homes and returning them to school.

Chemawa is still operational today, making it the longest-running Native boarding school in the United States. It’s housed in new buildings now, adjacent to the old campus, and still run by the federal government. However, the government no longer forces Native children to attend.

In an emailed statement an Indian Affairs spokesperson wrote that more than 75 Tribal Nations are currently represented by students at the Chemawa boarding school.

"The Bureau of Indian Education is proud of the diverse Tribal representation and honors Tribal heritage generally as well as the different Tribal cultures and values of its students."

P

art III: uncovering Charlie’s story

Back at the general store in Old Chemawa, where Willie, Ignace, and Charlie were trying to break in, a train traveling nearby rumbled loudly.

Henderson, the shopkeeper, peered out the window, took aim, and shot five times.

Spooked by the sound, the boys ran. Willie headed toward a cabbage patch. Ignace fled through the front.

Charlie ran a few steps, and then collapsed.

Henderson went downstairs to get more shells for his gun. When he heard someone convulsing, he called for help, and searched the grounds. He found Charlie’s small body, all 5’4 of him, slumped near a ditch.

A bullet had gone through his head, entering his right temple and leaving through the left.

Doctors, including the school physician George Fanning, operated on Charlie to relieve the pressure on his brain. Charlie died hours later.

To members of the Klamath Tribes of southern Oregon and northern California, Charlie’s death is a fresh wound and a reminder of the suffering the boarding schools caused.

Clayton Dumont Jr., chairman of the Klamath Tribes, said the intergenerational trauma caused by the boarding schools continues to harm his community, manifesting as “substance abuse or violence, and loss of connection to old cultural ways.”

“I personally was raised by a boarding school survivor, and many of the people here today, including other tribal council officers, were raised by the survivors of the boarding schools, and I can tell you it transfers from generation to generation,” Dumont said.

Klamath tribal members learned about Charlie recently, when tribal researcher Gabriann Hall connected with two researchers who had looked into Chemawa.

Hall had been researching Native boarding schools since 2019, two years after the Oregon legislature passed Senate Bill 13, which called for statewide curriculum on the experiences of Native Americans in the state.

“We knew we wanted to tell the boarding school story,” Hall said.

In February 2021, she connected with Eva Guggemos, an archivist at Pacific University in Forest Grove. At the end of a phone conversation, Eva made a stunning revelation.

“She asked me if I knew what the Klamath Tribes wanted to do with the bodies at Chemawa,” Hall said. Hall didn’t know the children’s bodies were still there.

Guggemos and longtime researcher SuAnn Reddick had pored over boarding school records. Their process was an exhaustive one: They combed sanitary files for names of students who had died, and compared those names with newspaper databases that may provide clues about where the students were buried.

They found that, from 1880 to 1945, at least 270 students had died in custody of the school. Of them, about 175 students were buried in the school cemetery. The remains of another 40 students were returned home near the time of their death.

The remains of 50 students remain unaccounted for.

“There is no grave marker, and we're not sure where they were buried,” Guggemos said.

Guggemos sent Hall the names of children buried at the Chemawa cemetery who were Modoc and Klamath, each part of the modern day Klamath Tribes.

On the list is Charlie Fiester — the persistent 12-year-old boy who kept fleeing.

Hall was surprised by the emotional impact of learning about these children.

“You think, ‘Oh, it was a long time ago,” she said. “Something that has become very, very evident is that it's not a long time ago, and the repercussions and that trauma is right here right now, today.”

In July 2021, Hall told Klamath Tribal leaders about Charlie and 11 Klamath and Modoc children buried at Chemawa. She has since shared his story widely, choking up each time she tells it.

“He's not a statistic. He's not a number. He's shá-amoks, is the word we use. He's family,” Hall said.

The tribe hasn’t found living relatives to decide what should be done with Charlie’s body, located about 200 miles away from the Klamath Indian Agency, at the school he desperately tried to leave.

“I cannot say for certain if Charlie Fiester was running home to his family,” Hall said, “but I can say he never made it.”

Editor's note: Variations of the spelling of Charlie Fiester's name appear in historical records. We determined his age based on intake logs, as his birthday was not included in historical documents that KUOW reviewed.