'Be fearless in pursuit of your goals. Be courageous in the pursuit of what you know is right.'

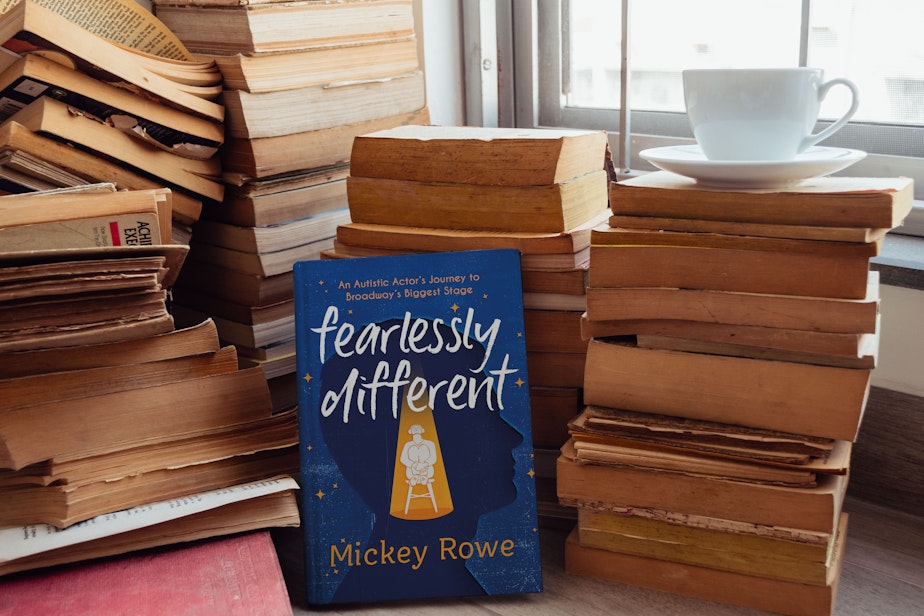

Mickey Rowe is the author of Fearlessly Different: An Autistic Actor's Journey to Broadway's Biggest Stage. He sat down with KUOW's Zaki Hamid to talk about his experiences.

This is an abridged version of the interview, you can listen to full conversation above.

Zaki: Why did you write this book?

Mickey: I wrote this book, because I think people often want so badly to fit in, that they forget what makes them stand out. So, I wrote this book, really hoping that it would help people to feel brave enough to stand out. I think often young, disabled people can really be taught by society, that they are a burden, and I really wanted them to know that you are not a burden. Your differences truly are your strengths. And the things that make you different are so, so valuable to all of us, and that you are giving the world such a huge gift when you share all of you.

There is so much really incredible, brilliant [academic] writing that everyone should read about disability, and about the disabled, lived experience. But I was getting really, really frustrated in life that even though there was all this really brilliant academic writing out there, I thought society at large didn't necessarily know about much of this didn't it wasn't on their radar. So, I tried to think about what small piece I could play to help change that and what I could do. And I thought, since I'm a storyteller, maybe I could just tell a really good story. And that would help people, who aren't already connected with the disability community, that would help them feel a connection to some of the information that I thought was really, really important for society at large to know about and learn about.

Zaki: In the first chapter of the book, you mentioned that sometimes you're like a fish and you that you keep moving and this is the quote that really struck me: “I finessed it enough to find the balance of moving through to focus and regulate myself but doing so where it doesn't concern or worry non-autistic people, non-autistic people seem to be easily worried by my movements.” Is that a big part of your life, accommodating non-autistic people?

Mickey: Absolutely. I think people who don't have disabilities have been unintentionally taught to sometimes feel really uncomfortable around disability. If you think about even young kids who maybe see someone who has a disability of visible disability or see someone who's maybe acting a little bit different, the parent usually pulls them away and says, “Oh, don't stare.” Or if they ask a question, “Don't ask about that. That's rude.” And I think it creates adults who feel really uncomfortable around disability, sometimes not even wanting to say the word “disability.“ I think about all the hoops we jump through saying “differently abled,” or “special,” or any of these other euphemisms to even avoid saying the word “disability” because we feel so uncomfortable around it. So, I think for a lot of disabled people, we often have to do a lot of work to make non-disabled people feel more comfortable around us.

You know, if you think about it, there are so many stories out there are so many books about disability. But very few of them are actually written by disabled people, or really include disabled people, I think about You Before Me, or I think about Wonder, all these books about disability. So, when talking to publishers and editors, trying to convince them why it was actually important that books about disability were written by disabled folks, that was definitely a big hurdle I had to jump through. But I think what it really came down to was, that people with disabilities, we don't just want to be readers, we don't just want to be audience members, or watch TV shows about disability. We want to be employed, we want to be active parts of the conversation about disability, and to help shape the stories about us from the inside, just like any other minority group would want to have a hand in telling the public stories that shape public understanding about their group.

Zaki: You were the first autistic actor to play an autistic character on a professional stage in the United States when you played Christopher Boone in the play The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime. The play, and the book that inspired it, have been lauded for its portrayal of an autistic team. But the author Mark Haddon, and the playwright who adapted the book for the stage, Simon Stephens, both are not autistic. So how did it feel stepping into that role?

Mickey: It was really complicated to be honest. In one way, it was so exciting because as an actor, I performed in Seattle at Seattle Children's Theatre and Seattle Opera, but never in speaking roles. So, Christopher Boone was not just my first leading role, it was my first speaking role. So, I was very excited in that way. But it was also complicated because, as Mark Haddon, the author says on his own blog, he won't talk publicly about autism. Because he says, it's not something he knows about. He says that he did no research into autism. In writing the book, the research he did was mostly just photographing Swindon Station, and another train station to get those parts accurately. But I think people with disabilities, we deserve a little bit more research than that, especially because books like that are often used to train police officers or used to train firefighters or even educators in the school system. It's really great to learn from actually autistic people as well. So, in playing the role Christopher, I was really excited that I got to humanize the role a little bit. And maybe sometimes when there were extreme behaviors that were shown without necessarily a reason behind those behaviors. I got to come up with an actual logical reason why might an autistic person actually do that? And how can I humanize it to show the why behind it a little more clearly, for the audience?

Zaki: We don't have white actors playing black or brown characters anymore, at least for the most part. But why do you think that we still see so many abled actors playing disabled characters and I’m wondering how that makes you feel?

Mickey: I think that one of the biggest things is, as I said earlier, people still feel uncomfortable looking at disabled people, thinking about engaging with disabled people directly. I know I've been in audition rooms where I can tell they don't really want me in the room, because they are nervous about what it might be like for them to speak to an autistic person. So, I think oftentimes, we're discriminated against in that way. But it goes larger than the entertainment industry that people with disabilities are just not included anywhere. It's been estimated that up to 85% of autistic college graduates in the United States are unemployed. And then even if you can get a job, up until right before the pandemic started in Washington state, there was no minimum wage for people like myself, people with disabilities. And nationally, still, the federal minimum wage is $7.25 per hour. For disabled people, companies can choose to pay one or two pennies an hour. So that's just the law. So, disabled people are being excluded everywhere across the table, not just in entertainment. But I think entertainment is particularly important because inclusion in the Arts, inclusion in literature, really leads directly to inclusion in life, we have a lot of power in entertainment, because we're how so many people get their information from us. So, if we can show disabled actors doing a really good job in a show, or in a movie, or onstage, or if we can read books by artistic authors and say, “Oh, that was a really good book, I am so glad I read that book.” We're then showing all the other employers across the country who might read that book, or see that TV show, they might think twice and think, “Oh, you know what, I can hire people with disabilities. People with disabilities can do professional work at the highest level. And we've no reason to discriminate against people with disabilities.”

I think the other piece too, is that disability is intersectional. Disability is, I think, really the most equal opportunity minority group out there. And everyone out there listening to this, should you be lucky enough to live long enough, you'll also likely get to join the disability community at some point in your life. But we're a pretty awesome prestigious club, so you can look forward to joining our club. But when you make the world more accessible for people with disabilities, when you use universal design, or read or promote stories that are written by people who actually have disabilities, you're really helping your future self too.

Zaki: You write about the fears that people have about autism, specifically, the fear that they might have a child diagnosed with autism, and there's a quote in your book, that says, “As if the only thing worse than a child dying, is a child with autism.” But what struck me about this is that you frame it differently. And you talk about something you call “Disability Gain.” And I'm wondering if you can talk a little bit about that.

Mickey: For full clarity, that's something I've stolen from the deaf community. The deaf community coined the term “Deaf Gain.” Often people would say, “someone has hearing loss,” right? And so the deaf community said, “No, they don't have hearing loss. They have deaf gain.” But when I talk about disability gain, what I'm talking about is all the things that make someone even more incredible because of their disability. I think often people with disabilities, their disabilities can make them more empathetic then maybe they would be without a disability. Their disabilities can make them better creative problem solvers. I think that disabled folks are some of the best creative problem solvers in the world because we have to be creative problem solvers everyday to navigate a world that wasn't designed with us in mind. There are so many things like that. I think that we can shift our perspective to see disability as an asset sometimes, rather than only seeing it as a liability.

Zaki: If and when you write another book, what would it be about? What else are you interested in covering?

Mickey: I don't know if I'm the person to write this book, but I would love to see a children's book that framed disability as something cool and fun and exciting. Because disabled people are smart, disabled people are powerful, we are sexy. And so often, when I read books to my kids, picture books, I'll see a character who's so sad because they have a disability. But luckily, a non-disabled friend saves the day and is the hero of the book to make them a little less sad. And I'll see narratives like that. I want to see picture books where the disabled people are their own heroes. And they were able to be their own hero in a really unique way because of their disability, not in spite of it. I want to see kids in wheelchairs, zooming down the hallway faster than their friends can keep up with them running down the hallway, or I want to see deaf characters who, because they know sign language, can tell jokes to each other in class while the teacher is looking the other way without their teacher knowing. Or can tell jokes to each other through the if one's outside their room, and one's inside the room through the windows, where we where we show all these awesome things that disabled kids can do that make disability an asset and make disabled people so, so smart and powerful.

Zaki: What are you working on right now?

Mickey: Right now, I'm actually working on workshopping a new show with a brilliant, awesome clown named David Shiner, who directed a whole bunch of the Cirque du Soleil shows. So, I'm working on his show with him, where we have a clown and an autistic person who seem so different, both of them. Maybe even inhuman in some ways to the audience at the beginning of the play. But as the play goes on, we realize they are both just trying and failing, and trying and failing so desperately at making human connection. And hopefully, by the end you're just left with two deeply beings on stage.