Puget Sound is the classroom for students at Maritime High School

Before she moved from Arizona to attend Maritime High School, Giselle Esparza said she was afraid of the water.

“Growing up in a desert, you’re not really used to the ocean and being on boats,” Esparza said.

Esparza recalled the first time she got on a boat at school. It was a longboat, and the rocking made her nervous. Now, she has a mantra before she climbs aboard.

“I usually tell myself, ‘You got this,’ and ‘It’ll be okay,'” she said.

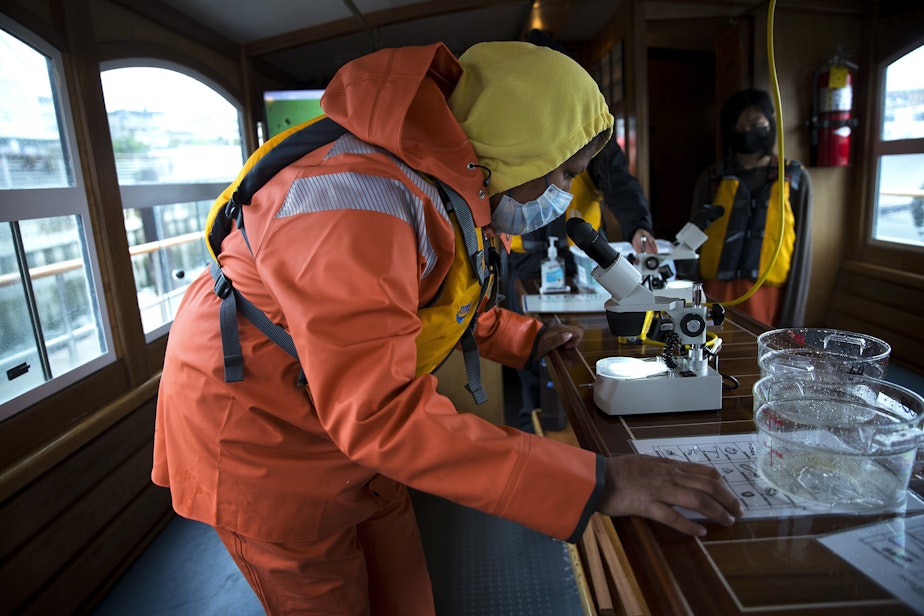

On a rainy, late-September morning, Esparza donned bright orange rain gear and hopped aboard the 40-foot long passenger ferry “Admiral Jack.”

Maritime High School is a new program designed to give hands-on experience to ninth graders (35 students) with marine science, maritime construction, and vessel operations.

The school and its partners — which include the Port of Seattle, the Northwest Maritime Association, and the Duwamish River Cleanup Association — hope that by giving students opportunities to learn on the water, they’ll consider a future in the maritime industry.

Seattle is home to at least 60,000 direct maritime jobs, according to Port of Seattle Commissioner Ryan Calkins. That encompasses jobs in shipbuilding, marine science, towboat operations and tourism, to name a few.

On this day, students are being introduced to the Admiral Jack. Over the next several weeks, they will work toward operating the boat with oversight from a professional crew, said Tyson Trudel, a maritime educator with the Northwest Maritime Center who also works with Maritime High’s students.

“We’re going to teach them how to do the pre-departure checklist,” Trudel said: Check the engine oil & Monitor the radios and the radar and all of the pieces that you need to do to navigate safely

Students here don’t receive letter grades; they set learning goals to track their progress. Instead of five days a week in classes, they spend two or three days a week on the water, or at port and marina facilities across the Duwamish River valley.

“We’re not necessarily handing them a manual that says these are all the things we need to do,” Trudel said. “We’re doing the, ‘Here’s an introduction to the boat, we want to safely take the boat out for six hours, what do we need to do to do that?’”

Later this fall, students will build prototypes of two different boats in the school’s woodshop. Eventually, after the school moves from their interim campus in Des Moines to a permanent location on the water, students will take the boats they built onto the water.

For Ethan Ma, the nontraditional approach to classes, and the focus on maritime, makes school a lot more interesting, which also makes his commute from Puyallup worth it.

“This school seemed more like things I would actually do and learn, and also project-based learning sounded much more fun than doing just a bunch of homework,” Ma said.

Ma said his favorite part has been exploring inside ships and learning how their engines work. He’s still considering whether he wants to work in the maritime industry, but he likes that he could go into the field after completing high school.

“I can at least get a job for sure, and then if I decide to change interests into a different field, I can do that relatively easily without worrying about financial issues,” Ma said.

There is money, and plenty of it, to be made in the industry.

According to the City of Seattle Office of Economic Development, the median hourly wage for positions that require a post secondary degree, like captains, ship mates, water vessel pilots and ship engineers sits above $39 an hour. Positions that provide on-the-job training but no formal education, like sailors and marine oilers, have a median hourly wage of $24.

Maritime High School’s arrival comes as Washington’s maritime industry stakeholders also confront a “silver tsunami” of a rapidly aging workforce.

According to the Port of Seattle, the average age of a maritime worker in Washington is 54 years old. By the time this class graduates in 2025, the Port of Seattle estimates there will be a shortage of 150,000 mariners.

Calkins, the port commissioner, said he started thinking about the wave of retirements and potential worker shortage a few years ago, after reading a news story about the demographic makeup of the maritime industry. Calkins said the ferry worker shortage that Washingtonians experienced this summer and fall is an example of the consequences the Northwest could experience as workers retire.

“If we don’t continue to feed new workers into the pipeline, we’re going to have to start pulling routes,” Calkins said. “That’s what we saw this summer — that routes had to be canceled because of a lack of available workers to work those routes.”

Maritime High School may also be a solution for the industry’s quest to diversify its workforce: In Seattle-King County, the maritime workforce is mostly male, and mostly white. According to a report published by the Port of Seattle’s Office of Equity, Diversity, & Inclusion, white people make up 78 percent of the industry, and men make up 74 percent.

While the school wants to create pathways for all students into the maritime industry, they especially want to provide opportunities for women and people of color.

One reason why Highline Public Schools was chosen as the host for Maritime High School is because of the demographics of its student body. According to data published by the district last school year, 15 percent of the student body identifies as Black, almost 15 percent identifies as Asian, and almost 40 percent identifies as Hispanic.

At the helm of Maritime High School is Principal Tremain Holloway. Holloway said he had limited exposure to the maritime industry before transitioning to his role at the school but quickly realized that while the maritime industry had plenty to offer in terms of job diversity, the workforce itself isn’t very diverse. He said he sees himself as a “conduit” to help students diversify the industry.

“Getting our kids, more specifically our students of color, into these roles ... that they may not even be aware of even though we’re surrounded by a body of water here in the Puget Sound,” Holloway said.

Student Emy Kissick appled to Maritime High School after reading about the school in a magazine. She’s on a sailing team and pondering a future as a ship’s captain.

“We need more women and minorities in the maritime industry. Most labor industries, there’s a lot of men and white people. It’s good that the school has such a modern and positive outlook on things like that,” Kissick said.

For humanities teacher Mia Mlekarov, working at Maritime High School is also personal: She grew up in a commercial fishing family in the Seattle area, and watched her mom work as a commercial fisher during the 1970s and 80s. She says women and people of color have always been present in maritime — but they've worked in the industry's lower wage positions.

"When we look at disparities in pay and we look at racial disparities in representation and decision making, those are things that need to change," Mlekarov said.

Now, she wants to help her students bring maritime into the 21st century.

"I want them to be able to appreciate what maritime is, and what it has done for our region, but also, empower them to feel like they have the ability to transform it."

Back on Admiral Jack, Ella Clark studied a water sample her classmates Giselle Esparza and Chloe Hedge-Pollock have pulled from Puget Sound. Clark was looking to see the kinds of plankton in the sample. But one of the creatures in the petri dish didn't match up with the reference sheets.

“As a scientist, if you discover something nobody has named before you get to name it,” Chrissy McLean, an educator with the Northwest Maritime Center, told the group.

They settled on “Ellington the worm.”

10/21/2021 Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled the last name of Port of Seattle Commissioner Ryan Calkins.