How one Northwest tribe aims to keep its cool as its glaciers melt

Record-breaking heat took a heavy toll on the Northwest this summer, from beaches to cities to mountaintops. In the Washington Cascades, some glaciers lost an unprecedented 8% to 10% of their ice in a single hot season.

For many residents, the snow and ice missing from the volcanoes poking up on the horizon was jarring. For others, it threatened their way of life.

The extremely hot summer of 2021 foreshadowed how unchecked climate change could ravage the fish that depend on cold water and the people who depend on those fish.

In Whatcom County, the Nooksack and Lummi tribes are taking steps to counteract the big melt and keep their salmon and their cultures alive.

This is part 2 of a 2-part series on the glaciers of Mount Baker. Read part 1: Northwest glaciers are melting. What that means to Indigenous ‘salmon people’.

1 of 2

Researchers for the Nooksack Tribe document the flow of Sholes Creek from the Sholes Glacier on Mount Baker.

1 of 2

Researchers for the Nooksack Tribe document the flow of Sholes Creek from the Sholes Glacier on Mount Baker.

"At the end of the century, there'll still be ice, but it'll be at the very top of the mountain,” Nooksack Tribe water resources manager Oliver Grah said while taking a break from documenting the retreat of the Sholes Glacier.

Rivulets of meltwater ran down its sloping icy surface where Grah, in t-shirt and crampons, and colleagues documented the thinning ice: 5 inches in one week in late September. It thinned by about 7 feet over the summer.

For now, the Sholes is one of 13 named glaciers on Mount Baker, Washington’s third-highest peak.

“Where we're standing right here will just be bare rock,” Grah said.

He said there’s not much the tribe, or anyone, can do to stop glaciers from melting, at least in the near term. So instead, the tribe is trying to deal with it.

“Our team's focus is more on the adaptation, resilience side,” he said.

T

he Nooksack River starts in the glaciers of the North Cascades, tumbles through lush conifer forests, then meanders past berry farms and pastures in the Whatcom County lowlands.

It’s really three rivers—the North, Middle, and South forks—that merge into one.

All around Puget Sound, salmon runs have been hammered by habitat loss, pollution, overfishing, and a warming climate. Runs in one river have been hit perhaps hardest of all: the South Fork Nooksack.

Puget Sound Chinook salmon, federally listed as a threatened species since 1999, have come closer to extinction in the South Fork than in any other river.

In 2013, just 10 Chinooks – the largest of the Pacific salmon and primary food of the Northwest's endangered orcas – returned to the South Fork.

When salmon swim up the South Fork, they are clearly visible, even when their fins don’t stick out of the water.

Unlike the other Nooksack forks, the South Fork is not fed by glaciers. As a result, its water is clear -- and warmer than the other forks with their milky glacier runoff.

“You don't have that cooling effect of glacier melt contribution to the river,” Grah said.

C

areful observers have known for generations this key difference between the rivers.

The Nooksack language name for the South Fork, and the village that once existed at its mouth, is Nuxw7íyem, or always-clear water. The Nooksack name for the Middle Fork and its village, Nuxwt’íqw’em, reflects that river’s glacial origins: always-murky water.

The murky glacier melt has helped shield the North and Middle forks’ eight species of salmon and trout, all of which depend on cold water, from the ravages of climate change.

During the record-shattering June heatwave, when the town of Nooksack hit 106 degrees, water temperatures in the South Fork rose 5 degrees while the North Fork only rose about 1 degree, according to Nichols College glacier researcher Mauri Pelto.

The mainstem Nooksack River runs past Abby Yates' backyard in Everson. She says the river that she and her Nooksack ancestors have all lived near behaved in ways she'd never seen before this summer.

"It was a raging, cloudy, muddy mess during August, which was very odd," Yates said. "I feel like maybe we were seeing more of that glacier melt."

Pelto says the Sholes Glacier, near the headwaters of the North Fork, has lost at least 25% of its volume since 1990, with the meltdown accelerating in the last eight years. He estimates it lost 6% of its volume in the summer of 2021 alone.

1 of 2

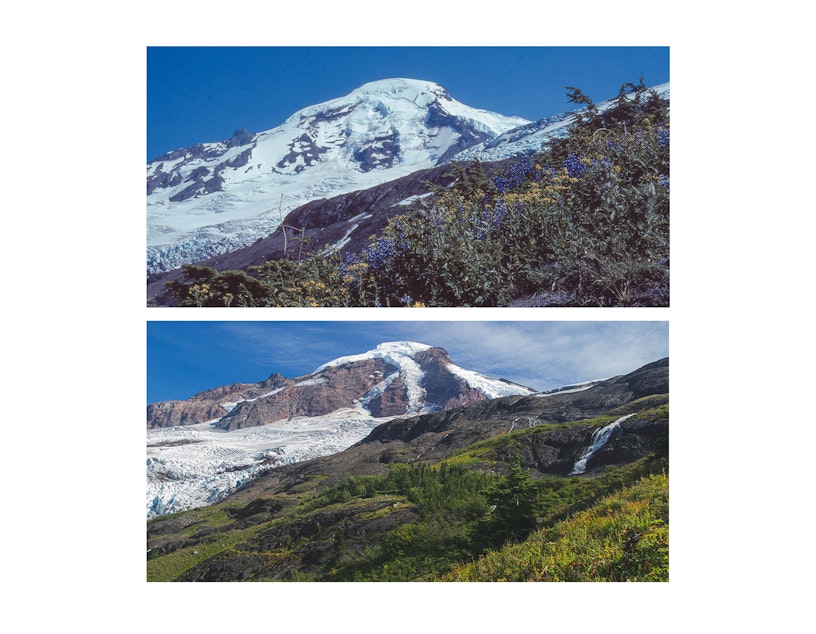

The north side of Washington's Mount Baker in August 1981 (above) and on Sept. 13, 2021 (below)

1 of 2

The north side of Washington's Mount Baker in August 1981 (above) and on Sept. 13, 2021 (below)

As glaciers and mountain snowpack shrink, they lose their ability to keep rivers cool, and researchers expect the North and Middle forks will have the same problems in coming decades that the South Fork already has.

Melting snow and ice keeps many Northwest rivers flowing and relatively cool each summer.

Half or more of the North Fork Nooksack’s flow in August is liquefied glacier.

“Our snowpack basically serves as nature’s water bottle,” said University of Washington climate researcher Harriet Morgan. “It allows us to store water when we have too much of it, in the winter, and then it provides us this nice reservoir in the summer when we’re not getting that summer precipitation.”

Without that reservoir, we get “more water when we don’t need it and less when we do need it,” according to Morgan.

In September, 2,500 Chinook salmon turned up dead in the South Fork before they could spawn. Biologists with the Lummi Nation say heat-loving bacteria killed the majority of that threatened species in the warm, low-flowing river.

“We don't have the snowpack that's needed to keep the water cool enough for the salmon,” Lummi Nation councilmember Lisa Wilson said.

Nooksack officials say the rapid changes on the loftiest peaks of the Nooksack basin demand changes throughout the rest of the watershed.

“We can't do anything about the recession of the glaciers and the change in stream flow and temperature due to the receding glaciers,” Grah said. “That’s why we need to take more of a watershed approach to promote more stream flow during the summertime.”

Salmon conservation efforts have traditionally focused on how many fish can be caught and how much habitat they have to grow up, migrate, and spawn in.

The Nooksack Tribe’s natural resources department has planted more than 50 acres of trees to provide cooling shade along creek and river banks. The state's salmon recovery plan for the basin says it needs another 2,300 acres of streamside forest for threatened salmon to recover.

The tribe has also engineered hundreds of logjams along the banks of the Nooksack rivers.

“The logjams provide some deeper pools for the salmon to rest and cooler temperatures so that they can make it to their spawning grounds,” Nooksack tribal member and planning manager Ross Cline Jr. said.

The Nooksack and Lummi tribes helped the city of Bellingham and its partners remove a dam on the Middle Fork of the Nooksack in 2020, giving access to 16 miles of spawning grounds salmon hadn’t reached in 60 years. Federal scientists estimate the dam removal could boost Nooksack River Chinook populations by a third.

R

estoring habitat for salmon may be less complicated than ensuring they have enough water.

The Nooksack River provides water for much of Whatcom County and supports $370 million annually in agricultural production, the most in western Washington, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Disputes over water rights have simmered in the Nooksack basin for more than 20 years, as rural and urban demands to use a limited resource have grown. In May, the state legislature funded a legal process known as adjudication to sort out the conflicting claims to the water of the Nooksack.

It’s not expected to resolve the conflict any time soon. The Washington Department of Ecology estimates it will take 10 to 20 years for final resolution of all water rights. The adjudication process does leave the door open for tribes and farmers to negotiate sooner over how much water must be left in-stream for salmon.

The lands of the South Fork have been heavily logged, with clearcuts and young trees dominating its modern landscape, leaving not only less shade, but less water for salmon streams.

Grah says a young forest of fast-growing trees sucks up more water in the summer, when rivers run low.

He wants to let Nooksack basin forests grow older before cutting them, or not cut them at all, as a way to help Nooksack salmon survive climate change.

“That would put more flow into the Nooksack River and would offset future climate impacts,” Grah said.

It could also help suck up the carbon emissions that are heating up the planet and melting the glaciers in the first place.

Morgan, the University of Washington climate scientist who is working with the Nooksack Tribe, said the tribe is a national leader in the field of climate adaptation: preparing for what can’t be prevented.

But there’s a problem.

W

hile Northwest tribes have treaty rights to co-manage fisheries with state governments, managing the land beyond the riverbanks is a different story.

The Nooksack Tribe controls almost none of the 500,000-acre Nooksack basin. Despite signing the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855, the tribe was only recognized by the federal government in 1973.

Today it has a reservation of 2.2 acres.

Cline Jr. says the latter fact shocks people from other tribes when he speaks at conferences.

“Afterwards, people would come up to me and they would say, ‘Did I hear you correctly? Did you say 2.2 acres?’ Yep, that's all we have for reservation.”

The federal government also holds about 2,400 acres in trust for the tribe and its members to use. Those trust lands are scattered in small parcels throughout the Nooksack basin.

“It's just a lot of lost opportunity for tribal members to be so restricted to various small areas up and down the river,” Cline said.

Now the tribe with around 2,000 enrolled members is working to buy back some of its long-lost land, with salmon among the main beneficiaries.

With the Whatcom and Evergreen land trusts, the tribe aims to create a lightly logged, 6,000-acre community forest along the South Fork. They’ve started raising funds to buy the first 500 acres of the Stewart Mountain Community Forest.

If the project comes together, it could leave more water in the river and help give Nooksack salmon a fighting chance in a warming world.