How to convince parents to vaccinate their kids?

With the recent measles outbreak in Washington, there has been an increase in lack of patience towards families that resist or hesitate to vaccinate their children.

This reluctance to vaccinate has shown up in two very different communities in Seattle – liberal white families and the Somali immigrant community.

How doctors in these communities address these low vaccines rates is also very different —with Somali doctors saying there needs to be a more open conversation around the community-specific concerns around vaccinations, so as not to alienate parents.

Ahmed Ali of the Somali Health Board is a practicing pharmacist and administers vaccines regularly. Ali said he has noticed a key difference in the patient-doctor relationship in the U.S.

In some countries, like his native Somalia, Ali said doctors tell patients what needs to be done, and patients follow accordingly. But here, he said he sees doctors providing pamphlets, papers and information and then asking the parent to make the final decision.

“What if the parent doesn’t understand what is on that piece of paper?” Ali said.

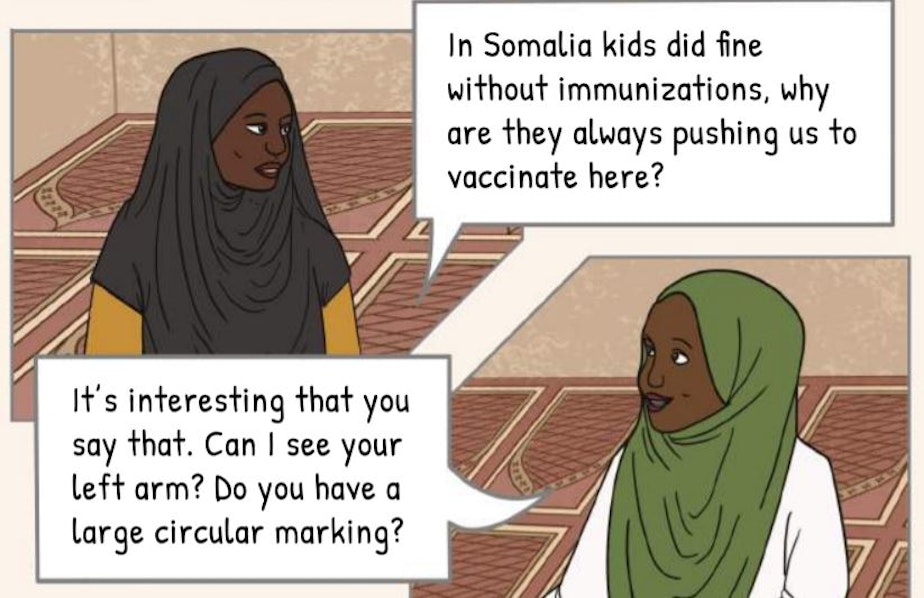

Seattle’s Somali Health Board recently released an illustrated, graphic-novel style booklet about vaccinations. It is for the Somali community, and includes culturally relatable terms and dynamics. But most striking is that the booklet treats the topic of vaccine hesitancy with patience.

A few years ago in Minnesota, a measles outbreak primarily spread within local Somali communities. That has led to the image that the Somali community is vaccine resistant.

Dr. Anisa Ibrahim, a pediatrician at Harborview Medical Center, cautions against that characterization. She said these parents are vaccine hesitant; an important distinction.

“People who are vaccine hesitant are mostly hesitant because they have not received the information that they need in a culturally congruent way in order to make decisions about their children’s health,” she said.

Kendal Watanabe, a health educator at International Community Health Services, which works with a large, culturally varied clientele, said that educational material about vaccinations has a language problem.

“They don’t know what is in a vaccine," Watanabe said. "People don’t understand how vaccines work.”

And when online materials or pamphlets from the doctor are filled with technical language, it is hard for anyone to understand — native English speaker or not.

Watanabe finds that parents are wary of vaccines because they assume the disease is still alive in the vaccine. She said that at ICHS there is an effort to make sure all educational materials explain vaccines simply – at a fourth grade reading level.

To address that information gap, Dr. Ibrahim said we need “cultural humility,” not “cultural competence.” Ibrahim said that right now, health care professionals assume that everyone comes into an appointment or check-up with the same information, and that there is a level playing field.

Ibrahim argues for a willingness to collaborate with community leaders to find out what actually contributes to vaccine hesitancy.

“I think the one misstep that health systems make often is that assuming that the health systems need to figure this out and then take it to the community rather than going to the community who have a lot of expertise within themselves and asking what should we do better,” she said.

Ibrahim underscored the importance of truly understanding a community’s concerns around vaccination. Part of that process is that larger health institutions should rope in community leaders and health practitioners who have a foot in both worlds.

“Communities value when people are interacting with their professionals because it shows that you are valuing the individuals in that community, their expertise, and the community itself,” she said.

The next step, Ibrahim said, is to figure out what method of education works best. One community might respond better to pamphlets, while another might want a presentation from the department of health. Yet another community may want to hear from their own community leaders.

Ali of the Somali Health Board said that many of the people he serves at his pharmacy live in neighborhoods where some resources aren’t accessible, resources that are basic social determinants of health. So when a community has to navigate access to food, clean air, water, then immunizations aren’t going to be top priority, he said.

For example, many in the Somali community weren't aware of the current measles outbreak, Ali said. But with carefully crafted messaging online and through social media, the community is responding to the concerns and has a better grip on the significance of a measles outbreak.

I

n the Seattle region, most schools do not meet the Washington State Department of Health’s prescription for a 95 percent vaccination rate.

Why that specific number?

“That is a good number where the disease doesn’t spread as well. Disease outbreaks are a lot less likely when we have a 95 percent coverage rate in the community,” said Danielle Koenig, Immunization health Promotions Supervisor at the state Department of Health.

Different diseases have a different “herd immunity”– that is the percentage of people who must be vaccinated to prevent the spread of the disease. But this number can be hard to reach.

Sometimes that is because of exemption laws. Washington state allows parents to not vaccinate their children on personal, ideological and religious grounds, also called exemptions. (The personal exemption is currently being challenged in the Legislature.)

Other times, it’s because the numbers just don’t add up. Low staffing levels can affect how vaccination documents are reported to the state. Then there is the issue of class size.

“For example if there are 10 students in that kindergarten and one has an exemption, they are only going to be able to get to 90 percent,” Koenig said.