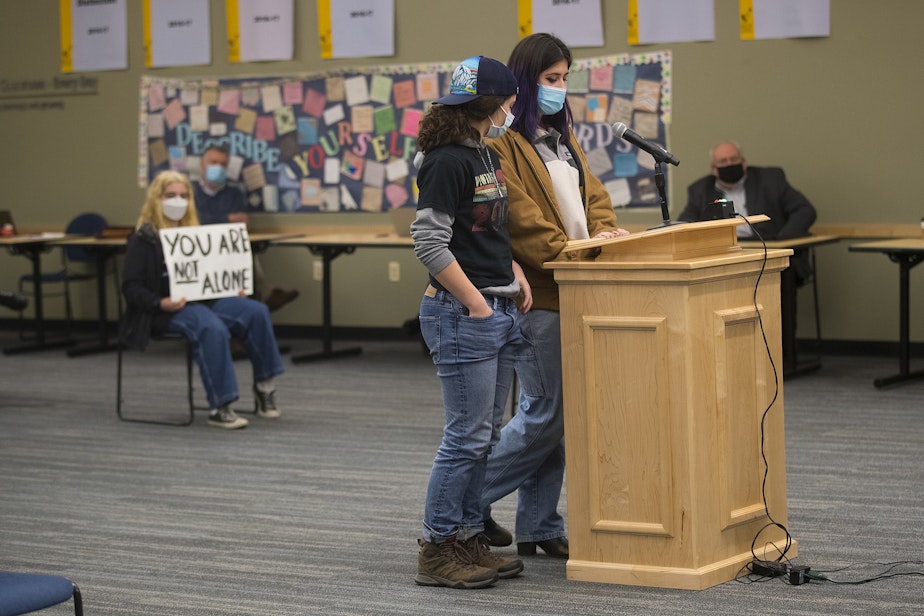

I was assaulted, this Seattle teen told school leaders, but no one kept her abuser away

The students’ chants reverberated through the wood-paneled walls at the John Stanford Center for Educational Excellence, where Seattle Schools board members were meeting.

Inside, 14-year-old Zirahuen Herrejon-Crutcher stood at the podium and said that a former “best friend,” also a freshman, had groped her during the summer. They had been lying on a trampoline, when he put his hand up her shirt, and fondled her for 15 minutes. She said she froze. Later, she said that she was terrified to see him at Ballard High School, where they both attended.

Zirahuen is among more than a thousand teenagers in King County who have in recent weeks protested their school districts, saying administrators are slow to investigate, resulting in some victims being stuck in class with their abusers.

School administrators respond that their hands are tied: Federal law says all students are entitled to an education, and their privacy. They cannot kick someone out of school after being accused of abuse; a process must play out.

In the past, administrators have asked those alleging harm to stay mum while they investigate, worried that the accusations could unsettle other students. But this new generation, raised with #MeToo, and armed with social media, is unapologetic about criticizing a bureaucratic process that forces them to see their abusers every day.

Z

irahuen was lying on the trampoline with three of her close friends outside her home, hours before the sun would rise on that early June day. The teens were under blankets, and cuddling as they sometimes would, Zirahuen wrote the King County Superior Court. When one of her friends put his hand up her shirt and groped her, without her consent, she began to panic, trying to process what was happening.

For days, that night on the trampoline weighed on Zirahuen and she became depressed, she said. When her parents noticed something was wrong, Zirahuen disclosed what happened.

“I still felt as if I had invited it or messed up in some way,” Zirahuen wrote. She said her parents explained that “it was in no way my fault and that (the freshman) had crossed a line when he did not ask for consent to touch my body.”

As teens speak out about instances of abuse, educators are mulling over ways to prevent it from happening in the first place.

Nicole McNichols, an associate teaching professor in Psychology at the University of Washington, believes that one step would be to teach affirmative consent. That's the clear, voluntary, and active agreement between all parties engaging in sexual activity.

“I'm 46 years old and when I was in college, unless you were screaming out ‘NO’ it was assumed during any kind of sexual experience that you were consenting, and that simply cannot be the standard,” McNichols said.

She said the protests emerging from high schools around Washington state mirror outcries on U.S. college campuses over the last decade.

This generation is saying, “Enough is enough,” McNichols said.

People born within Gen Z (1997 to 2012) are emboldened about gender identity, believing innately that gender is fluid and that people don’t all fit within the “arbitrary binary of man versus woman,” McNichols said. At the same time, she said, this generation is more accepting and celebrating of female sexuality.

McNichols said it’s about recognizing feelings of empowerment that arise from personal agency when making sexual decisions.

“That is now more at the forefront of thinking and is really how young people now are sort of conceptualizing sexuality,” she said.

The protests are consistent with the Me Too movement, McNichols said, which was ramping up as many of these high school teens were in their formative years. The Me Too movement is one among women who decidedly took a stand against sexual abuse and harassment by making their allegations of sex crimes public, for all to see, often when there was no institutional recourse for the accused.

Elements of the Me Too movement, which gained traction in Hollywood, are now seen among high school students protesting in hallways and courtyards, some of them publicly naming their abusers, others organizing on social media.

T

en weeks after the trampoline incident, Zirahuen stood before a judge in King County Superior Court, and asked that the court approve a sexual assault protection order and keep the freshman from returning to Ballard High School.

The judge agreed to the order, to oblige the freshman to stay at least 500 feet from her home, but allowed him to return to school. The judge approved rules that would prevent the two from bumping into each other on campus.

The protection order did her little good, Zirahuen said. It didn’t prevent the two students from crossing paths, and seeing him gave her panic attacks.

KUOW reached out to the freshman’s parents, who declined to comment. In court records, the freshman said that he had his hand up her shirt, but that she had encouraged him.

Zirahuen and her mom told Ballard High School leadership about the summer encounter, in which Zirahuen said she was groped without consent.

Administrators changed the class the two students had together, and drew up a separate school agreement, which instructed the students to turn around and go the other direction when they saw each other at school, Zirahuen said.

“They said they wouldn't enforce it, because the only way they'd be able to enforce it is if they were walking with him all day,” Zirahuen said, and that they wouldn’t enforce the protection order granted by the judge. Her mother, an immigration attorney, has hired legal representation to navigate the school and criminal system, she said.

Zirahuen said she saw the freshman in the halls, and once, her mom saw him leaving campus 15 minutes after the final bell, when the protection order required the freshman to be off campus before the final bell rang.

As of mid-December, Zirahuen has filed four police reports over protection order violations.

D

uring a protest at Ballard High School in early November, before hundreds of her peers, Zirahuen shared her experience as a sexual assault survivor. It was a pivotal moment for her, she said, a way for her to call attention to a system she wanted to change. She felt less isolated when she heard other students sharing similar accounts.

Zirahuen said she never mentioned the name of the freshman who she said harmed her over the summer. KUOW is not naming the freshman because he is a minor. However, after the protest ended, students came to Zirahuen to offer support, and said they had figured out who the freshman was on their own.

Hours later, Ballard High School Principal Keven Wynkoop wrote to parents about the protests, and said responding to student reports of sexual assault is complicated, given that a number of them happen off school grounds — and fall outside of their jurisdiction to investigate and discipline.

“Our focus is on making a police report, contacting parents and supporting the victim in a variety of ways, based on what they report would be helpful. I sympathize with the difficulty of sexual assault survivors having to see their attackers at school and cannot imagine having to face that trauma over and over again.”

Across Lake Washington, at the Bellevue School District, Art Jarvis, interim superintendent, wrote in response to Bellevue’s groundswell of protests, that schools cannot violate student privacy. He said that while there was no tolerance for sexual assault or harassment, school districts may not skip essential investigations, or neglect “due process protection deserved by every person.”

That doesn’t mean school districts can’t take measures to protect survivors as investigations are underway, said Shannon McMinimee, a former attorney for the Seattle and Tacoma School Districts.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights issued a letter in 2011, providing guidance to colleges and K-12 leaders in adhering to requirements on sexual harassment included within Title IX, a federal anti-discrimination law that applies to all public schools and colleges.

Included in this letter are remedies school districts should consider when responding to sexual harassment or violence — some of them measures that could be used as school investigations are underway, the letter says.

Among them: Providing an escort for a complainant, to ensure safety as they move between classes; ensuring the complainant and alleged perpetrator aren’t in the same class; moving the complainant or alleged perpetrator to another school in the district.

The letter says that schools might have an obligation to respond to student-on-student sexual harassment that happened away from school, if the impacts of the sexual harassment are being felt in the school setting.

“For example, if a student alleges that he or she was sexually assaulted by another student off school grounds, and that upon returning to school he or she was taunted and harassed by other students who are the alleged perpetrator’s friends, the school should take the earlier sexual assault into account in determining whether there is a sexually hostile environment.”

The letter says the school in this hypothetical scenario, should also protect the student assaulted off campus “from further sexual harassment or retaliation” from the perpetrator or their friends.

School districts’ obligation under Title IX is separate from what families may do through courts or law enforcement, McMinimee said.

During former President Donald Trump’s administration, this letter was rescinded, and the U.S. Department of Education, under Betsy DeVos at the time, put federal regulations pertaining to sexual harassment under Title IX, in place. The rules called for a higher level of proof when investigating sexual assault and misconduct and said schools did not have to investigate any off-campus, non-school related incidents.

“We can continue to combat sexual misconduct without abandoning our core values of fairness, presumption of innocence and due process,” DeVos said announcing the rules, according to news coverage on the regulations.

However, work to dismantle these changes began after President Joe Biden’s inauguration.

Locally, a Seattle Public School’s task force convened in 2019, to examine the district’s sexual assault and reporting policies, and ensure they comply with regulations of Title IX, and Office for Civil Rights guidance. Their recommendations will go before the Seattle School’s Board of Directors next spring.

But even if change is on the horizon, King County high school students told KUOW bureaucracy moved too slowly to address the issues they experienced today, and that the gap seemed too wide between policy and what they felt needed to change.

McMinimee said improvements are long overdue.

“The systems should be and should have been robust 10 years ago,” McMinimee said, pointing to the guidance issued by the Office of Civil Rights in 2011.

Z

irahuen reported her assault to police; she got a sexual assault protection order; she told her principal. And yet, she said, she still feels unsafe, and dismissed.

“When you're a kid, you have these places where you feel like you should be safe and protected,” Zirahuen’s mother, Chelan Crutcher said. “Of course always their home, and I think another place where a lot of kids feel like they should be protected and safe is at school.”

A week after the protest at Ballard High School, two of Zirahuen’s friends were called into an assistant principal’s office, and told to sign no-contact agreements, she said. Her friends were told that if they spoke about the sexual assault, they could be suspended, reads an email Crutcher sent to high school leaders.

The no-contact agreement came after one of these students flipped the freshman off, the email says. Zirahuen’s mother filed a complaint with the district, alleging that some school leaders created a hostile environment for Zirahuen.

Five days later, on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving, Principal Kevin Wynkoop went on leave. Tim Robinson, spokesperson with the Seattle School District, said he was unable to divulge the reason for Wynkoop’s departure, or comment on if the school district could enforce protection orders between students at the same school.

“Every report of sexual assault or sexual harassment is dealt with confidentially in a manner that is appropriate for the specific circumstances presented,” Robinson wrote by email. “As such, it is not possible to provide a broad answer to your questions.”

Since filing the complaint with the district, Zirahuen said things have improved.

Student activism on the issues hasn't ended.

Fifteen days after the Seattle School Board meeting at the John Stanford Center for Educational Excellence, there was another, and students returned again, to draw attention to the overhaul they say is needed in the district’s handling of sexual assault and harassment complaints.

“No matter what challenges you hand us, we will get through it,” Dylan Carney-Woods, a Ballard High School sophomore said. “Any uncertainty you have, we’ll fix it. And any questions you have, we will answer them. As you all requested, the community has spoken and we will not stop until we get justice.”