Students chain selves to smokestack to light climate fire under UW

One building gives the University of Washington most of the school’s sizeable impact on the global climate.

Inside the UW steam plant, boilers the size of school buses capture energy from burning natural gas. Just outside, a 20-story smokestack puffs out enough carbon dioxide from the boilers to make the university one of the state's biggest climate polluters.

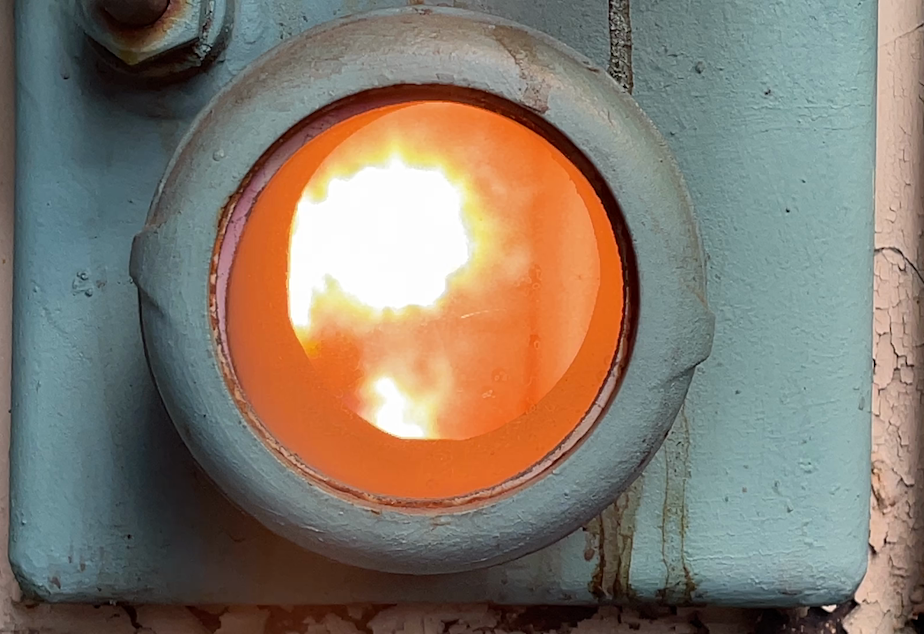

Mark Kirschenbaum runs the plant. He opened a lid on a tiny glass window for a visiting reporter to see the flames whipping around inside one of the boilers.

“You're looking at a 2,000-degree flame,” Kirschenbaum said. “By the time this exhaust gas leaves the boiler, it's down to 200 degrees. That's fairly efficient. All that energy is transferred into the water to make steam, and that steam carries the heat to the buildings.”

10 secs

A peek inside a gas-fired boiler at the University of Washington in Seattle's steam plant, the main source of heat and carbon dioxide emissions at the university, on May 15.

10 secs

A peek inside a gas-fired boiler at the University of Washington in Seattle's steam plant, the main source of heat and carbon dioxide emissions at the university, on May 15.

Steam heat from the plant circulates around the campus through more than 7 miles of claustrophobic, pipe-lined tunnels.

David Woodson was hired to convert this carbon-belching system into something more climate-friendly.

The university is facing both financial and activist pressure to do its part for the global climate and stop relying on fossil fuels much sooner than it now aims to.

“What we need to do on the campus to change such a massive system like this, we need to be taking action, like right now, and we are,” said Woodson, in a cramped tunnel about 80 feet beneath the Husky Union Building.

8 secs

A time-lapse of a walk through a small portion of the 7.5 miles of steam tunnels beneath the University of Washington campus in Seattle on May 15.

8 secs

A time-lapse of a walk through a small portion of the 7.5 miles of steam tunnels beneath the University of Washington campus in Seattle on May 15.

The first step of that big change, Woodson said, is converting from steam to hot water. The lower temperature will allow electric heat pumps to do the job that gas-fired boilers do today.

Many homeowners and small businesses have started switching from gas or oil heat to electric heat pumps, especially with new tax breaks available for doing so.

Woodson said it’s different for a massive system like UW’s.

“There's no flip the switch and you have something different six months from now,” Woodson said. “It's not like you can go to Costco and buy it and plug it in, right?”

In his previous job, Woodson oversaw a switch from steam to hot water at the University of British Columbia. That step alone took six years. He said it might be possible to complete in four years at UW.

Many big polluters in Washington have had to start paying to keep soiling the atmosphere in 2023.

The list of major polluters that have to buy “carbon allowances” for their planet-heating emissions include fuel suppliers and gas utilities.

It also includes organizations you might not expect, like the University of Washington and Washington State University. UW’s main campus emits three times, and WSU’s main campus two times, the 25,000 metric ton annual threshold to be regulated as major polluters under the state’s new cap on carbon emissions.

Rather than paying for them, more than 100 of the state’s biggest climate culprits, including oil refineries, power plants, and pulp mills, have received their carbon allowances from the state for free. After lobbying by industry, state legislators chose that approach to keep manufacturing jobs from leaving the state.

The universities got no such special treatment and are facing an immediate hit to their bottom line if they keep polluting.

If UW’s Seattle campus keeps burning gas at its current rate, the university will have to pay about $4.5 million a year in carbon fees, based on the price at the state’s first quarterly carbon auction in February.

University of Washington sustainability director Lisa Dulude called the carbon fees “the kick in the pants that we needed.”

“Now there's a real monetary penalty to UW, and we expect it to increase year over year,” she said.

The University of Washington aims to be 95% decarbonized by the year 2050.

“I would love to find a way that we could move faster than we are, but it's just not an overnight task,” Woodson said.

Student protesters say their school is not acting with the urgency the climate crisis demands.

“You all remember the 2050 chant?” UW senior Brett Anton asked a rally he was leading on the university’s Red Square plaza. “U-Dub, U-Dub, you can’t hide.”

“2050 is a lie,” the crowd shouted back.

Protesters with the UW-based group Institutional Climate Action rallied and marched across campus Friday, May 19, to demand faster action.

“UW doesn't want to get off fossil fuels until 2050. Can we get a boo?” Anton, a political science and climate science major from Tacoma, asked the crowd. “Boo, a lot of institutions think that's enough.”

“The world is going to exceed 1.5 C [warming] at some point in the next five years,” Anton said. “Every bit of additional greenhouse gas we put into the air is poison in our lives.”

In addition to rapid decarbonization, the students want their school to stop taking fossil-fuel money and stop steering graduates to careers in climate-harming industries.

“How long are we going to feed our students into the fossil-fuel industry and turn our backs as our futures get devoured?” chemical engineering major Frances Yih of Woodinville asked outside the university’s career center. “We have no more time. We have no space for fossil fuels. We need to cut ties with big oil now.”

Outside the construction site of a Boeing-sponsored engineering building, where speakers denounced war profiteers’ role in the climate crisis, one bystander had had enough.

A motorcyclist forced his way through a roadblock the protesters had created on the main loop road through campus.

The biker, unlike the Metro bus also stopped by the protest, could have done a U-turn and detoured around the blockage.

Instead, he rumbled aggressively toward the rally until a yellow-vested protester on its perimeter blocked his path and grabbed his handlebars. He fell off his big touring hog, then chased the protester, threatening to hit him while hurling f-bombs.

“Get a goddamn life!” the biker said. “You got a bus that's trying to work,” he said. “I got a family to take care of.”

“I'm out here for my nephew,” the protester replied. “By 2050, there's going to be 1 billion refugees.”

“I don't give a fuck, dude,” the biker said. “Get the fuck off the road, homie.”

After a couple minutes of heated arguing, the biker saw that the cluster of protesters exercising their freedom of assembly was moving off the road to its next destination, and the potentially violent conflict dissipated.

27 secs

First-year UW student Amber Pesce of South Carolina speaks to a rally for decarbonization while standing on the base of the school's smokestack on May 19.

27 secs

First-year UW student Amber Pesce of South Carolina speaks to a rally for decarbonization while standing on the base of the school's smokestack on May 19.

At the steam plant, six students and one other person chained themselves to the smokestack that is UW’s biggest source of planet-heating carbon dioxide.

Amber Pesce, a first-year student from South Carolina, spoke to supporters while standing on the base of the smokestack.

“Delaying action would lead to such devastating increases in climate damages that justifying delay is not ethically possible,” Pesce said. “Because you know what is possible? Ninety-five percent greenhouse gas reductions by 2035.”

These young activists even took a desperate measure for their generation: They left a voicemail.

Brett Anton dialed up university president Ana Mari Cauce.

“So I just wanted to let you know where we are,” Anton said into Cauce’s voicemail. “We're chained to the power plant right now. We're all here to call for the UW to move off of fossil fuels by 95% by 2035.”

He invited Cauce to visit them at the smokestack, which she did several times over the weekend, even bringing protesters oranges at one point.

Cauce held talks with them on Monday. University spokesperson Victor Balta said UW shares the activists’ goals but can’t commit to a faster timeline on a project that might cost $500 million until it knows more about the feasibility of faster action.

“President Cauce shares the students’ goal and is looking forward to working with them to achieve it,” Balta said by email on Tuesday.

After three nights at the steam plant, the protesters chained themselves to the centrally located Suzzallo Library, so more students and staff would see them.

Meanwhile, university sustainability officials say they are putting together a proposal to decarbonize UW operations in Seattle, Tacoma, and Bothell by the year 2035, in line with what the protesters are calling for.

“We're literally trying to go as fast as we possibly can go,” David Woodson said.

Sustainability director Lisa Dulude said the school was also beginning to address, for the first time, its indirect emissions, like those from people commuting to campus and from making cement and other products the university purchases.

The University of Washington markets itself as a leader in climate science and in embracing sustainability.

How quickly it actually makes its operations climate friendly is ultimately up to Cauce and her bosses, the 11-member UW Board of Regents appointed by the governor of Washington.

Full disclosure: As KUOW listeners often hear, KUOW is a service of the University of Washington. The station leases gas-heated office space in Seattle’s University District and does not receive heat from the campus steam plant. While KUOW has undertaken projects over the years to improve energy efficiency and is currently replacing its fluorescent lights with LEDs, operations director Dane Johnson said KUOW has no plans to switch away from its gas heating or otherwise decarbonize its operations.