What led to Whatcom oil-train disaster? Investigators eye equipment, tracks, even sabotage

Even though an oil train derailed and burned for hours that day, government officials and oil-industry critics alike say the Puget Sound region got lucky on December 22.

The mile-long train full of fossil fuel happened to spill near two refineries with specialized firefighting brigades and far from any population centers, shorelines or salmon streams.

No one was injured when the 108-car train derailed in the small town of Custer, Wash., north of Bellingham. But about one tanker car’s worth of crude oil — 29,000 gallons — was lost, either up in smoke or spilled on the ground.

What caused the fuel carrier to go off the rails probably won’t be known until the FBI and other agencies finish their investigations months from now.

Even so, KUOW has been able to piece together much of what happened on the tracks that morning and some of the questions that tight-lipped investigators are pursuing.

Part 1 of this KUOW investigation captured the tense moments as firefighters raced to evacuate a town and BNSF Railway workers rushed to stop more tanker cars from igniting.

Here, Part 2 investigates possible causes of a disaster that could have been much worse.

Disclosure: BNSF Railway is a financial supporter of KUOW.

R

ail is a relatively safe and energy-efficient mode of transportation. Still, trains can derail, and their cargo spill, for many reasons, from poorly maintained tracks to speeding to sabotage.

At least six government agencies are investigating the Custer crash. The FBI is leading the investigation into the causes of the crash.

Key questions for crash detectives include: why would this train, moving just 7 miles an hour, derail, and why would its supposedly puncture-resistant tankers rupture at such a low speed?

“It will likely be some time before we have answers to questions regarding the cause of the derailment and fire,” Whatcom County Executive Satpal Singh Sidhu said in a written statement.

Human error and track conditions are the leading causes of U.S. rail accidents, according to Federal Railroad Administration data, while problems handling oil and other hazardous materials are the most common federal safety violations on U.S. railways.

Retired National Transportation Safety Board investigator Russell Quimby said crash detectives would plug data from the Custer locomotive’s event recorder, similar to the “black box” recorder on an airplane, into a simulator to recreate the train’s complicated motions as it derailed.

Quimby likened a long train to a giant “Slinky” toy that stretches and contracts as it accelerates, decelerates and moves around curves. During a sudden deceleration, such as a train’s emergency brakes activating, cars mid-train can be pushed off the rails by the cars behind them.

“Usually at slow speeds, an undesired emergency will cause a train to stop, but it won’t cause cars to buckle or derail like that,” Quimby said. “I wouldn’t expect a derailment, especially like that on a straight track. It seems kind of strange to me.”

In 2017, an Amtrak passenger train derailed on brand-new tracks near Olympia, Washington, killing three, after it went through a 30 mile an hour curve at 79 miles an hour.

“Speed can affect the severity, but trains can derail at any speed, even one or two miles per hour,” Herb Krohn with the International Association of Sheet Metal, Air, Rail and Transportation Workers said.

Inspecting the tracks

In 2016, a train carrying the highly volatile fossil fuel known as Bakken crude to Tacoma derailed and caught fire in the Columbia River Gorge. It led to the evacuation of the town of Mosier, Oregon, and contaminated groundwater 600 feet from the river.

Federal investigators found that Union Pacific’s poorly maintained tracks caused the train to go off the rails.

After that disaster, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee pushed, unsuccessfully, for daily inspections of tracks used by Bakken oil trains.

“Without these increased inspections, Bakken crude oil trains should not be allowed to travel through our communities,” Inslee wrote to the head of the Federal Railroad Administration.

In Custer, the BNSF tracks had last been inspected by the Federal Railroad Administration on Dec. 15, one week before the crash, according to Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission spokesperson Dean Pertner.

“To our knowledge no defects were found,” Pertner said in an email.

Spokespeople for the Federal Railroad Administration declined to comment on that inspection.

BNSF spokesperson Courtney Wallace said the rail company had inspected its tracks near Custer 12 days before the crash, on Dec. 10.

“Our inspector took no exceptions to the track’s conditions and found no defects,” Wallace said in an email.

Wallace said BNSF inspects that track monthly, in line with federal requirements.

Depending how a railroad owner classifies a given stretch of track, the Federal Railroad Administration requires track inspections anywhere from monthly to twice weekly. Wallace said the track in Custer is a connector, not a main line, with only monthly inspections required.

“Safety is not just a buzzword for us at BNSF,” Wallace said the day of the crash. “It’s a foundation of what we do.”

BNSF has fewer accidents or safety violations per mile than the freight-rail industry average, according to federal data.

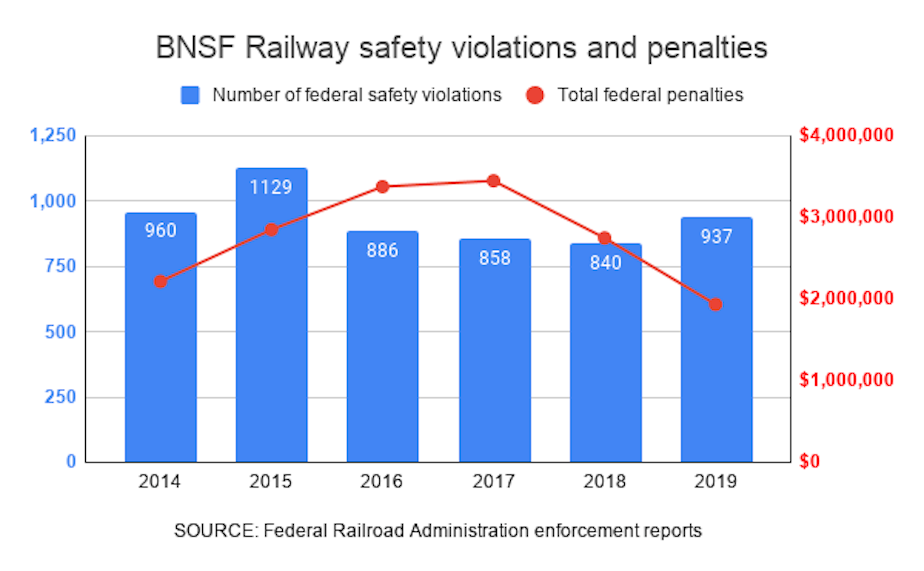

BNSF committed 937 safety violations in 2019, the most in the previous four years, according to the Federal Railroad Administration. The agency issued $1.9 million in penalties against BNSF that year, the least in the previous six years.

With BNSF earning $23.5 billion in revenues in 2019, those penalties work out to less than one hour of revenue for the nation’s largest rail company.

“Federal fines are so small, they are statistically insignificant for [major freight] carriers,” Krohn said in an email. “They no longer serve as a deterrent for safety compliance.”

1 of 2

BNSF Railway pays $2.8 million a year on average in safety penalties and settlements to the Federal Railroad Administration.

1 of 2

BNSF Railway pays $2.8 million a year on average in safety penalties and settlements to the Federal Railroad Administration.

Older cars, thinner walls

After a train carrying Bakken crude exploded and killed 47 people in Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, in 2013, U.S. regulators required railways to start using stronger, less fire-prone tanker cars.

The National Transportation Safety Board is analyzing how well the railcars in the Custer disaster performed.

According to Phillips 66 spokesperson Melissa Ory, 9 of the 10 Bakken crude tankers that derailed in Custer were older cars, retrofitted to meet the tighter federal safety standards enacted in 2015.

“Those improved rail cars were indeed the rail cars that were involved in this incident, and that likely contributed to minimizing the amount of oil that was released,” David Byers with the Ecology department said the day of the disaster.

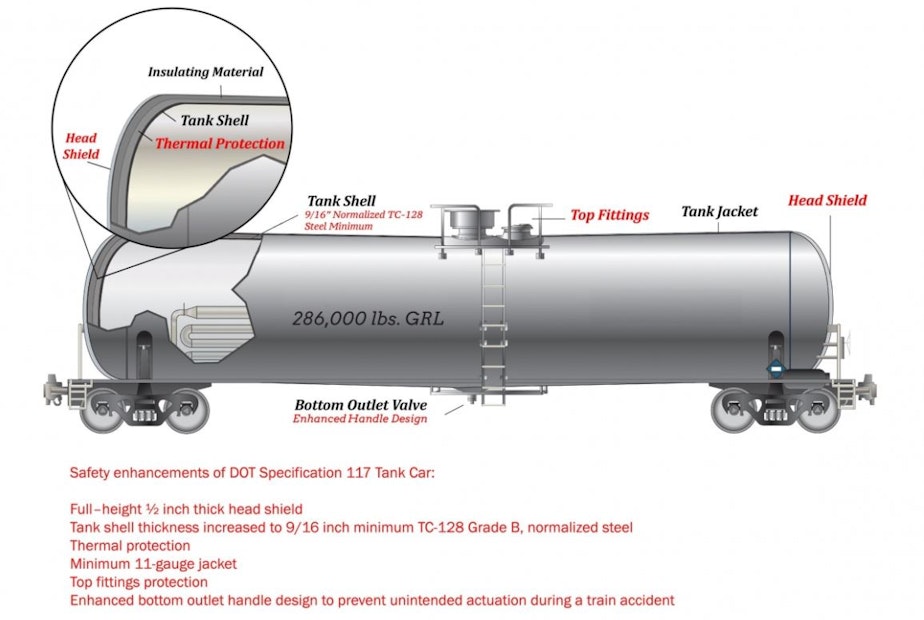

The retrofitted cars, known as DOT-117Rs, feature multiple safety improvements over their previous versions, though they are not as beefy as the newer DOT-117J cars built since 2015.

Among other differences, the steel shells of the retrofitted cars can be 1/8 of an inch thinner than on the new cars (7/16 of an inch versus 9/16 of an inch).

The sides of newly built tanker cars are designed to resist punctures from collisions at up to 12 miles an hour. The reinforced ends of the cylindrical tanks are supposed to resist punctures at up to 18 miles an hour.

In an email, Ory said Phillips’ retrofitted cars performed as well in derailments as brand-new cars, though an industry-funded study she provided contradicts that claim. The 2019 University of Illinois study of oil-train accidents found that the retrofitted cars could be twice as likely to spill oil as the newly built ones.

“The thicker the tank car wall, the less likely it is to release [oil] in an accident,” the Washington Department of Ecology concluded in its 2020 rail transportation safety study.

Oil-train critic and author Justin Mikulka said in an email that in his view, “If a train was going under 10 mph with the new cars and that still resulted in tank ruptures and fire, it is very clear these tank cars are not adequate to protect the public from this risk of this dangerous volatile oil that Washington state tried to regulate.”

In May, the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration overturned a 2019 Washington state law that would have prohibited transporting highly volatile oil, like Bakken crude, without pretreatment to make it less explosive.

Mikulka said tanker cars – both the new ones and the older retrofits – have ruptured repeatedly in recent years.

Wallace said BNSF doesn’t own the cars in the oil trains that ply its tracks.

“We have been working with our individual customers to facilitate getting the newest and safest tank cars, currently the DOT-117Js, in service sooner on our railroad,” she said.

Could it be sabotage?

Investigators are also looking into the possibility that this crash wasn’t an accident at all, but an act of sabotage.

Just before midnight on Nov. 28, about three weeks before the Custer disaster, two women were spotted kneeling on BNSF tracks near the Bellingham airport, about 10 miles south of Custer, according to federal prosecutors.

Whatcom County deputies arrested the pair and said they found a “shunting” device – a bit of wire attached to a railroad track to interfere with trains’ electrical signals – installed near where the two women had been kneeling.

The women allegedly had rubber gloves, insulated copper wire and a wire brush with them.

Federal prosecutors charged Samantha Brooks and Ellen Reiche of Bellingham with a terrorist attack on a railroad facility. The two pleaded not guilty on Dec. 17 and have been free on bond.

Brooks’ private attorney and Reiche’s public defender did not respond to interview requests.

Brooks and Reiche have their trial date set for Aug. 30.

Until then, they must stay in western Washington — and not trespass or loiter on any railroad tracks.

Federal prosecutors said someone had placed wire shunts on BNSF tracks in Whatcom and Skagit counties 41 times since January 2020, apparently in protest against construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline through Indigenous territory in British Columbia.

Prosecutors said shunts placed one night in October triggered the emergency brakes on a train carrying flammable gas and made part of the train uncouple from its locomotive. The FBI’s Joint Terrorism Task Force has been investigating the shunt incidents.

Government and BNSF officials declined to say whether there is any link between the Custer crash and the alleged track tamperings earlier in the year.

“The investigation is ongoing,” BNSF’s Wallace said. “I’m not going to speculate on the investigation.”

Rail experts expressed doubts that a wire shunt could have caused the Custer train to derail.

“All that’s going to do is tell the signal system that that section of track is occupied,” rail-accident investigator Russell Quimby said. “That shouldn’t have any effect, especially at that low speed, other than the engineer seeing a red [stop] signal ahead.”

“There’s no indication that there was any kind of signaling system issue,” Seattle-based union official Herb Krohn said. His union represents BNSF Railway workers.

With the Custer oil train sitting unoccupied on the tracks for close to two hours next to a rural road, Krohn said there would have been time for someone to tamper with the train itself in ways that could have been more damaging.

Leaving a train full of explosive fuel unattended in “high-threat urban areas,” including a 10-mile radius around Seattle and Bellevue, is prohibited by the U.S. Transportation Security Administration, but it’s allowed everywhere else in Washington state.

In January 2020, an anonymous post on the anarchist website itsgoingdown.org claimed credit for disrupting rail service on BNSF tracks in Whatcom County with wire shunts.

It called BNSF’s lines, which continue into Canada, “a primo target for blockages and slow downs in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en.”

Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs have fought construction of the multibillion-dollar Coastal GasLink pipeline through their territory in interior British Columbia, while the Wet’suwet’en’s elected tribal council has welcomed the pipeline.

Nearly 57 million barrels of crude oil, just under a third of all crude oil refined into petroleum products in Washington, arrived by rail in the year ending Sept. 30, according to the Washington Department of Ecology.

Ships and pipelines both carried slightly larger shares of the state’s oil.

Environmentalists say, however the state’s most-used fossil fuel is delivered, spills are inevitable.

“There’s truly no safe way to move crude oil, whether by rail or vessel or truck or pipeline. We see these accidents all the time,” said Bellingham-based environmental activist Matt Krogh with the nonprofit Stand.Earth.

Krogh said he could see the smoke plume from the Custer train fire from his home, 13 miles away.

“The real choice for safety is to move to 100% electric transportation as fast as possible,” he said.

The Association of American Railroads says the nation’s rate of rail accidents involving oil or other hazardous materials has dropped 64% since 2000.

For now, agencies investigating the Custer crash are mostly tight-lipped.

FBI spokesperson Amy Alexander declined to answer questions about the investigation.

“We are still working with our partners to determine the cause of the accident and have not ruled anything out,” she said in an email.

The Federal Railroad Administration expects to finish investigating the Custer crash in April.

KUOW environment reporter John Ryan loves getting tips and documents. He can be reached at jryan@kuow.org, the encrypted heyjohnryan@protonmail.com or the encrypted Signal app at 1-401-405-1206 (whistleblowers, never do so from a work or government device, account or location). Snail mail is also a secure way to reach him confidentially: KUOW, 4518 University Way NE #310, Seattle, WA 98105. Don't put your return address on the outside.