What workers want: How industries hollowed out by the pandemic are getting folks back

We’ve all seen the help wanted signs, had slow service at our favorite restaurant, or maybe a long wait in the ER. The markers of the Great Resignation are inescapable. Nearly 100 million workers in the United States quit their jobs over the past two years. Now, employers are trying to figure out how to get them back.

KUOW talked to hiring managers and workers in some of the industries hit hardest by the pandemic about what it takes to get folks back to work.

Better pay, flexibility, and workplace innovation

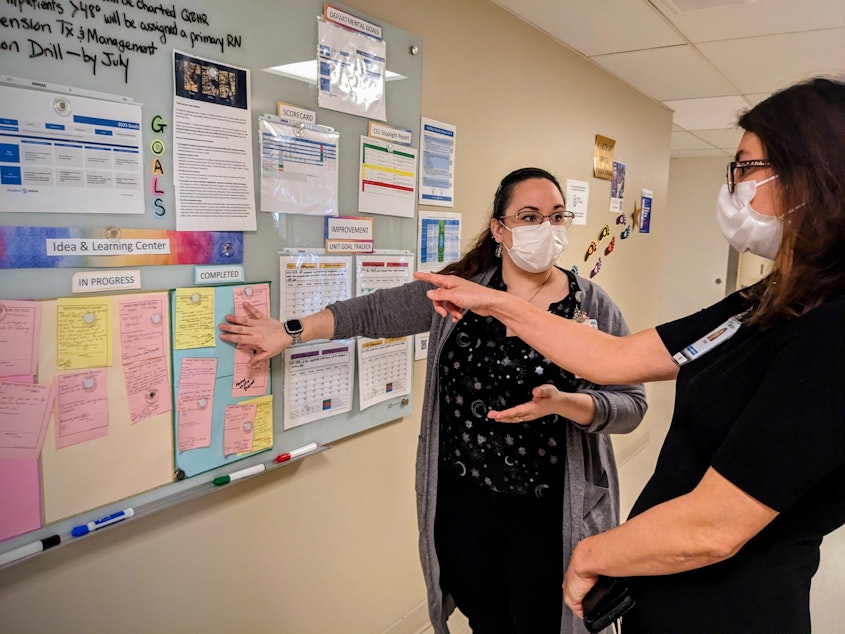

Staffing was a top concern Renee Rassilyer-Bomers heard visiting nursing units recently at Swedish First Hill hospital. As Chief Nursing Officer for several Providence Swedish hospitals in Seattle, it’s her job to make sure there are enough nurses.

It’s been an uphill battle since the pandemic, but she’s starting to make progress. Her hospitals have reduced turnover by about 3%, which she says is a big improvement.

Rassilyer-Bomers attributes those gains to investments aimed at addressing financial stress, burnout, and mental health of nurses — all challenges that were exacerbated by the pandemic.

Swedish nurses and other staff are getting a 20% raise thanks to a newly negotiated contract.

“Prior to our renegotiation, nurses wanted more pay, and equitable pay, particularly in comparison to the travel nurses,” Rassilyer-Bomers said. “That was something that really resonated. Flexibility was also huge. The hospitals are implementing new safety measures and mental health resources to help nurses cope with the daily stresses of their jobs.

And Swedish is hiring more support staff and coming up with other creative solutions to take some work off of nurses' full plates.

Melissa McCarthy-Bates is an antenatal nurse at Swedish First Hill. She said that her unit is close to meeting its hiring goals during Rassilyer-Bomers’ rounds.

“I'm in a race, I hear, with one other unit to potentially be fully staffed,” she said. “I'll only need two more nurses after July.”

But like most hospitals, Swedish Providence still has a long way to go before it reaches sustainable staffing levels. The goal is to bring turnover below 20% by the end of the year.

Rassilyer-Bomers says innovation is key to Swedish’s strategy to reduce employee churn. For example, Swedish is exploring ways to offer staff nurses some of the perks of travel nursing. That includes flexible scheduling and expanding teams that can float from hospital to hospital.

Workplace innovation is also the key ingredient to retaining employees at Jude's, a cocktail bar and Cajun restaurant 10 miles south of Swedish First Hill.

A sense of ownership

Mark Paschal was bartending at Jude's when the opportunity to buy the restaurant arose.

“I never wanted to be a boss, but I don't also don't ever want to work for anyone,” he said. “That's why I went into bartending, because it's the closest thing that I could find to something like that.”

When Paschal’s business partner moved away, he decided to turn Jude’s into a worker-owned co-op. It had long been a dream of his and the pandemic added a sense of urgency to make it a reality.

“All sudden there was a purpose to me in working, that I hadn't felt for a very long time and a purpose for having bought Jude's that I felt had kind of gone absent,” he said. “It was the most incredible experience, all of a sudden, to have an opportunity to live a dream and find people to work with rather than find people who could work for me.”

Employee ownership is rare, but it’s gaining popularity as younger generations seek to democratize their workplaces.

Industry experts say the idea is gaining traction in Washington in particular. State lawmakers tried to pass a bill this session that would make it easier for companies to become worker-owned, but it failed to advance by the legislative deadline.

Critics of the co-op model say it’s impossible to get anything done when decisions are made by consensus. But Jude’s employees say it’s working for them.

The restaurant has had relatively low turnover since going co-op, compared to high rates seen across the industry.

After six months at Jude’s, employees can pay $1,000 to become partial owners. If they leave, they sell their stake back. Major decisions are made democratically, including what to do with profits and losses.

Libby Huse joined Jude’s in February. Thinking it would be like any other restaurant job, Huse didn’t necessarily expect to stay long-term.

That changed when they saw the opportunity to become an owner of the restaurant.

“The ethos of Jude's is not anything like I've seen before, because of the way that its owned, because of the way that it's operated,” Huse said. “It leaves a lot of room for emotional and mental investment, with a return.”

Mental health resources

Mental and emotional wellbeing is a priority for workers across industries hit hard by the pandemic, like education.

The U.S. faces a shortage of about 300,000 teachers and staff. Burnout is one factor driving the teacher shortage in Washington, according to the office of the superintendent.

Teachers were on the frontlines during the pandemic, adapting to remote learning and fielding frustration from parents. Even as Covid rates drop, teachers continue to navigate tricky dynamics as the classroom becomes the latest battleground of the culture wars.

As associate superintendent of talent strategy at the Lake Washington School District, Joy Ross is in charge of getting teachers back in the classroom.

“Teaching has changed,” she said. “It is a noble profession. And it's hard. And the rewards are amazing. And it's hard.”

She says today’s teachers are particularly interested in programs that address mental health, like a new teacher mentorship program that pairs new hires with seasoned veterans for their first two years.

“Ensuring that there are professional development opportunities, there's mentorship, that there's this real collaborative approach, I think that makes a difference as people are becoming more intentional about the choices that they make for where it is that they choose to work,” Ross said.

A new labor landscape

In today’s tight labor market teachers, hospitality workers, nurses, and other workers deemed essential are demanding employers evolve to meet the moment.

That means emotional support, raising wages to match inflation, providing flexibility, and giving employees the opportunity to feel like stakeholders at work.

Hiring managers across industries say these needs pre-dated the pandemic. The percentage of workers voluntarily leaving their jobs has been steadily increasing each year since 2009, with the exception of 2020.

But the pandemic exacerbated these challenges, like so many loose threads in the fabric of our social safety net. Now, it will take creative solutions to mend them.